Johanna Adam.

PSM Berlin.

THIS IS WORSE

BY JOHANNA ADAM

AM I SAFE? The question is as complex as it is elementary. The answer depends on a number of factors that concern all of the mosaic stones of our current living situation. We cannot get an overview of all of them; not all of them matter equally. And yet we can answer quickly, because in the end it essentially points to the individual feeling of each of us: “Do I feel safe right now?” Ariel Reichman raises this question as a kind of preface to his exhibition.I AM SAFE can be read on the neon lights outside in front of the gallery building. Or I AM NOT SAFE—depending on the answer we ourselves give by pressing a button in the exhibition or online at iamnotsafe. If we press NO, all of the letters of I AM NOT SAFE light up. If we press YES, the small word NOT goes out: I AM SAFE.

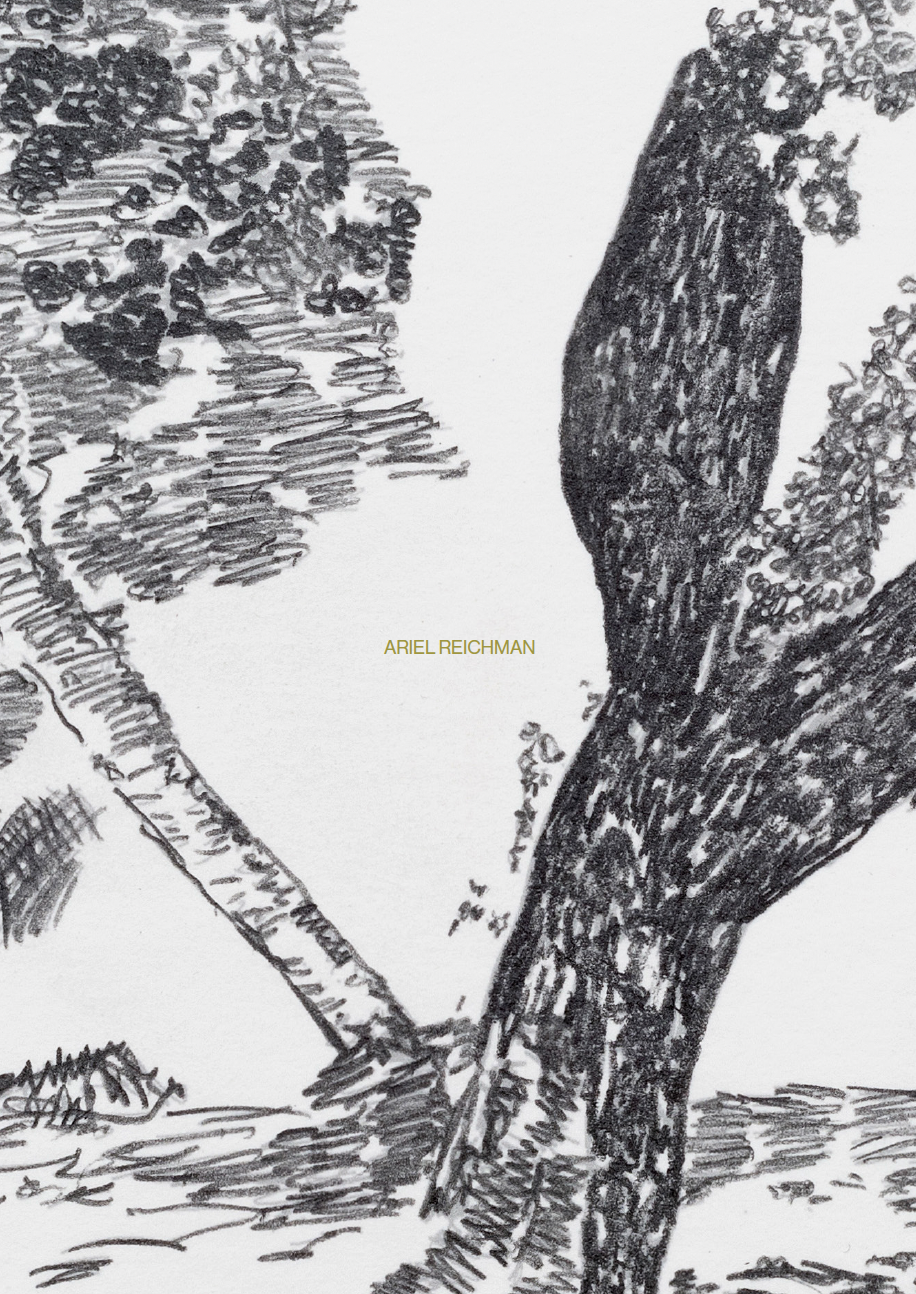

Our emotional state becomes visible—and so subjectively and temporarily as the question per se allows. It cannot be made objective and can scarcely be differentiated, because if we were to answer it in the absoluteness with which it is posed, the rigorous answer would always have to be: No, because there is no total safety. But I can certainly feel safe. At least sufficiently safe to answer the question with YES, even if itis/was only for the moment and in reference to those aspects that are foremost for me rightnow.The works of Ariel Reichman are often about inner states and individual constitution. This is also true of the series I Still Have to Be Strong, which consists of tree trunks and branches that he gathered in the forest near his studio. The tree as a metaphor of strength and resoluteness becomes here a fragile body that has deep traces of burns in several places, produced by the artist himself.In those places, the solid wood becomes brittle, thin, and fragile. The visible fragility seems that much more astonishing to us because the former strength of the branches is still visible. This image can easily be related to a human level: The stronger a person seems to us, the more we are perplexed by signs of vulnerability. In view of society’s debate over attributions of masculinity, this contradict can be read as a reference to clichés that still dominate: Visible weakness is the final taboo for men.Collective insecurity and its effects on the individual play a role in Ariel Reichman’s work above all when he addresses the themes of war and violent. In his series Pre/Post Disasters of War, he takes up the drastic depictions of violence that Franciscode Goya presents in his Desastres de la guerra (The Disasters of War). Goya’s aquatint etchings, produced between 1810and 1814, shows the horrors that people—in this case, Spanish and French people—did to one another during the Napoleonic occupation. Their unsparingness but also the criticism of state and church connected to that made it impossible to publish these sheets during Goya’s lifetime. The etchings were first published in 1863. Esto es peor (This Is Worse) is the caption to one of these scenes from Goya’s Desastres.

The abysses of human nature are in a position to cause unbearable suffering, worse that one’s own imagination permits. Ariel Reichman studied Goya’s etchings intensely and reworked them artistically. In a series of ninedrawings, he takes up scenes but removes all of the people from them. Only the barren landscape—often scarred by violence just like the human protagonists once visible there—can now be seen. Reichman meticulously fills out the parts of the landscape that had previously been covered with scenes of violence and thus heals them in a sense. Do these images offer consolation on account of the seemingly pacified landscapes? If the absence of violence can only be achieved through the absence of people as such, then we can surely not allow ourselves to be fooled by the deceptive calm in Reichman’s drawings: They open up the space to reflection on human nature, which is capable of supreme cultural achievements and at the same time opens up the deepest abysses.Another of the artist’s series is closely connected to war or, more precisely, to military culture. And here, too, interestingly, landscape plays a connecting role. In his Military Landscapes, Ariel Reichman makes military insignia—primarily from the Israeli armed forces—the basis of highly abstract landscapes. The insignia often represent stylized landscape elements that served as a background for military motifs, such as tanks, fighter planes, or raised flags. In his images, Reichman removes them and focuses attention instead on the formalized landscape, on its colors and characteristics. What do such insignia convey beyond military decoration? Is the depiction of the landscape an appeal to the patriotism of soldiers? Are the colors based on political color codes? Reichman is addressing here not least questions of aesthetics. Everything that is produced is subjected to conscious design. The criteria on which they are based depend on the context and intention. A military insignia must beclearly identifiable and easily distinguishable; it has to be expressive, to convey certain attributes, and ideally serve as identification. That is no small challenge for a designer, especially as the pictorial field and color repertoire are limited. Thework Military Landscapes has a strong personal component in the artist’s biography. He served in the Israeli military, where he repeatedly encountered various insignia. For the artist, questions of design and context are linked here. It is above all the contrast between the naive, almost cheerful adaptation of the landscape and the martial content for which it is the backdrop.

Ariel Reichman’s work is often based on personal experiences. In his reflections on what he has experienced, seen, or been handed down, however, something universal is always concealed as well. He recognizes transferable patterns and using specific examples raises question that can also be asked in other contexts. Not infrequently, the artist also connects to collective memories and experiences. In order to make them visible, he finds strategies for minimizing and maximizing, isolating and emphasizing, and translating into other media. Daily political events play a smaller role than our fundamental human condition does: What is our essence as human beings? Ariel Reichman finds the signs for our conditionality, for our dependence on external and internal factors, in everyday experience.

Hila Cohen-Schneiderman.

Petach Tikva Museum of Art.

TO BE PRECISE UNTIL IT HURTS

BY HILA COHEN-SCHNEIDERMAN

In his solo exhibition, 1200 Kg Dirt, Ariel Reichman plays the role of an artist, a gardener, a ‘bereaved mother.’ The garden which he has been tending in the last few months is a strange, beautiful and disturbing garden, containing plants and sculptures, paintings and objects. More than a garden, it is a state of mind, an attitude; a kind of parallel universe in which the Petach Tikva Museum’s Collection Gallery has become a mausoleum, where plants breathe life into the sculptures. It is a garden where the speech is weaker than the silence, and the body precedes the mind.

Reichman’s exhibition engages with the existential paradox that underlay the erection of Petach Tikva’s Bet Yad LaBanim (a building commemorating the fallen soldiers) right next to Independence Park – the struggle between the culture of remembrance and nature, which always tries to grow wild. His work addresses the national aspect of the museum’s collection and examines bereavement, pain and loss alongside the myth of heroism. The cult of death depends on figurative and dramatic representations, whereas Reichman proposes to replace them with a connection with nature as a life - affirming possibility.

The garden he creates relies, both materially and visually, on vegetation common in cemeteries, particularly in military cemeteries in Israel. Reichman’s tending activity typifies the work of mourning carried out by bereaved families. This is not melancholy work, but rather a continuous ritual which keeps the mourner alive and in a certain sense becomes the purpose of his life. It is in this mental state that the families tend to the little gardens on the graves of their loved ones – which, on the one hand, look as uniform as soldiers, and on the other, blossom with plants and personal effects. This work of mourning contrasts with the official ‘Commemorative Enterprise’, as the families’ struggle to particularize their mourning highlights the failed nationalization of the fallen, and their existence on the line between the personal and the collective, the political and the intimate.

This tension also underlies Reichman’s gardening activity, having started the working process in his private studio before transferring his garden, planted on 1200 kg of dirt, into the institutional exhibition space. Once he had brought up sculptures and paintings from the collection’s underground storage into the gallery, his actions became subordinate to the instructions of the restorer, or clashed with them. He was required to dim the garden’s lights and use pesticides, in order to kill the insects infesting it and threatening the life of the collection. Despite this, the garden seems to have grown out of control, starting to climb up the sculptures installed in it, as if to realize their own fantasy of coming back to life. Moreover, when Reichman covers the sculptures physically, with sand or vegetation, he also metaphorically covers their mythical aspect. This is not a violent or oppressive act, but rather a natural ecosystem, in which nature offers something different from the paradigm that posits human intervention in commemoration. And in this artificial garden, in which sunlight is florescent light, plants grow out of tiles, the rustle of the ventilator turns the wheel of the weathervane, and the black crow ominously watches the youth, it is evident that every gesture in Reichman’s work has a sculptural value. The understanding that everything here is sculpture creates a poetic/cruel equation which relies on the unifying logic of the military cemetery, in which a private is buried beside a colonel; thus Dov Feigin’s iconic sculpture, Palmahnik, receives the status of a weathervane or a protruding cactus threatening to jump off the shelf ’s springboard. In this ecosystem, a sculpture or a painting has the same status as a plant, the hierarchy is finally leveled out, and a proposal is formed that exposes the gap between the mythic and the ‘natural.’ For myth is not a thing of nature, but rather something that is built and constructed.

Lydia Korndörfer.

Kunstverein Arnsberg.

PLAYGROUND

BY LYDIA KORNDÖRFER

The outdoor sculpture “Playground” has been realized as central piece for Ariel Reichman’s solo exhibition “In Limbo” (21.09.2020 - 6.12.2020) at Kunstverein Arnsberg.

The first element of "Playground" – a field of car tires – was installed in the garden of the Kunstverein. Three further stations – a field of palisades, a jumping wall and dodging walls staggered one behind the other – are located in the Ruhr valley about one kilometer from the Kunstverein. Embedded in an idyllic river landscape, it can hardly be imagined that these outdoor sculptures are inspired by military training camps. They appear completely removed from their original context and yet offer visitors and passers-by a playful insight: Whoever crosses the walls and palisades could, through their own physical experience, establish an abstract imagination of the reality of military service. A sign with a QR code links to a homepage which provides more information about the sculpture’s background and was set up especially for the project. Online it will also be documented how the installation could be activated in a performative way.

With "Playground" Ariel Reichman continued to explore a subject ultimately linked to his own biography: The artist, who himself served as a soldier in the Israeli army, examines the military environment for its formal qualities like he did, amongst others, with "1, 2, 3, Boom" (2016), his "Military Landscapes“ series (2020/2021) or his "Clouds“ series (2016).

The sculptures have been realized with the kind support of the Artis Grant Program, tollerei, the Hochsauerlandkreis and the city of Arnsberg.

Curated by Lydia Korndörfer

https://www.playground-kunstvereinarnsberg.com/

Field of tires:

One needs to skip from one tire to another by landing only in the empty spaces. The field consists of 40 tires.

Dimensions (entire element)

253 cm (L) x 632 cm (W)

Field of palisades:

Jumping from one palisade to another, one’s balance will be in test! The field consists of 42 palisades, each with a diameter of approximately 15-20 cm, about 40 cm high and installed with a distance of one meter apart from each other.

Dimensions (entire element)

566 cm (L) x 566 cm (B)

Kicking wall:

The red line on the wall marks the height one needs to kick with the foot in order to have enough momentum to jump over the wall.

Dimensions

180 cm (H) x 210 cm (W) x 30 cm (D)

Dodging walls:

As in a game of hide and seek, these six walls simulate narrow spaces and corridors. One must move sideways between the walls without being detected.

Dimensions (each wall)

160 cm (H) x 330 cm (W) x 15 cm (D)

Bettina Steinbrügge

Kunstverein Im Hamburg.

HOW MANY TIMES…

BY BETTINA STEINBRÜGGE

When I was asked to write this text, I could not help but think of Jacques Rancière and his dictum in The Aesthetic Unconscious. The strength of Ariel Reichman’s work can be found in its encouragement and admission of ambiguities, its subtle showing but also not-showing, which sometimes takes one to the limit of one’s own categories, one’s own seeing, and one’s own certainties. Take the series of photographs Oranges (2010), which shows details of an orange grove. The choice of colors, composition, and pictorial space are balanced and harmonize with the perfect images that surround us daily. There is one difference, however, since the photographs were taken in the dark; the oranges are illuminated. Normally, oranges offer an image full of hope, happiness, and satisfaction. But the intellectual shock is not far away, because it is not the sun shining here; rather, this perfect surface is seen from its dark side. At this point, it is important to consider the significance of oranges in Israel. With these photographs, Ariel Reichman approaches a symbolic reality in which the orange tree marks the beginning of a new settlement, ideology, or society. The Jaffa orange is probably the most famous citrus fruit and also an essential component of the origin myth of Israel. It is full of stories from politics, economics, and manipulation, in which one can observe the rifts and commonalities of Israeli and Arab history. But to return to the beginning of the story: Oranges were introduced to the region by the Arabs before the Jewish settlement. Orange farming was later perfected and developed by Israeli agricultural experts. At first a shared fruit, it quickly became synonymous with the new state of Israel—especially as a successful export and a symbol of the expansion of Israeli territory. Its Palestinian origin was increasingly suppressed and is as good as forgotten today. The Jaffa orange became a positive symbol of a flourishing Israeli state. Finding an approach to history is not simple, the search for one’s own identity even less so. Ariel Reichman, who was born in South Africa under apartheid and is now an Israeli citizen, finds himself in a difficult situation—just like the author of these lines, who as a German citizen has just as little right to take a critical view of this history and who carries around with her the guilt of previous generations, without really knowing how she is really supposed to deal with it or how the corset of society can permit an open view of social connections at all. A language has to be found for this rift, since silence is not a solution either. Ariel Reichman makes this possible by subtly depicting ambiguities. In his work, the social is, however, always also the personal, as can be seen in the work Hold Me (2015). What happens when you encounter in an exhibition space a pile of stones that fit comfortably in one hand and on which the words “Hold me” appear? You follow the instruction, take one in your hand, and walk through the exhibition. It feels good to carry this stone, which fits snugly in the palm and has no edges. This quite positive feeling soon takes on a double edge, however. Should I perhaps also throw it to express my displeasure at something? A brief impulse runs through my body. But then I think about the fact that the whole stack of stones represents the weight of the artist’s body. The weight of the stack is sixty-seven kilograms in all, so metaphorically I am carrying part of the artist through the exhibition. In this performance, the weight or burden of a human being is distributed across several people: a collective effort, as it were. In recent months, I have frequently encountered paving and other stones in exhibitions. It seems as if the time has come for a revolution, time to oppose the impositions we encounter every day in newspapers, on television, and in social interactions. Reichman does not make it easier for me to live out this feeling, since his stone is physical and profoundly personal. Can I just throw it now, or must I, on the contrary, allow caution to prevail? Life is complicated, and many traditional categories of coexistence simply no longer exist. I just have to let that recognition stand as is.

Reichman’s works, realized across nearly all possible artistic media, are based on the concepts of empathy and vulnerability; that is, they concern everyone personally. The works are marked by his everyday experiences and for that reason are also mercilessly honest and approachable. The press release from Zeppelin Universität aptly reads: “Subjective memories, daily rituals and fantasies are the basis of his artistic concerns. He is interested in the spiritual state of phenomena, their possibilities of succeeding well or failing totally. For Reichman, the intimate is also the political, and that concurrence can enable one to try to understand politics and one’s own environment by means of oneself, no matter whether it is fiction or truth, historical reality or fable.”2 The installations Tea for the Master, Coffee for the Madam (2014) and Maria (2016) follow the traces of his earliest memories in South Africa. Starting with childhood photographs, he sets out in search of the nanny who cared for him in his earliest childhood under apartheid. The journey becomes a search for himself, but it also asks how South African society has changed since apartheid ended. In the forms of both video and performance, the artist looks for this person but does not find her. She remains in the background, and thus as invisible as she already was at the time: a part of society that functions but does not adopt any particular position and is thus not seen. In a society where individuals are increasingly preoccupied with their own visibility, this is perhaps difficult to understand. But it is only a marginal aspect of Reichman’s inquiry, here. The point of these works is to say with great empathy and circumspection something that should really remain unsaid. The point is to erase one’s distance from these events in order to become aware of one’s own involvement. The abstract status between a political reality and one’s own emotional being is obvious, but it is all too often forgotten. Reichman calls this artistic work between one’s presence and the physical effect thereof “conceptual Expressionism.” Here Rancière comes into play again, invoking Freud on why he was concerned with art: “It matters little whether the story is real or fictive. The essential is that it be univocal, that, in contrast to Romanticism’s rendering the imaginary and the real indiscernible and reversible, it set forth an Aristotelian arrangement of action and knowledge directed toward the event of the recognition.”3 Freud preferred the form of the silent word, that is, of the symptom, which is the trace of a story.4 This would be a good description of Reichman’s practice: he creates objects and artistic artifacts that evoke feelings of confusion and conflicting emotions. Often they cannot be resolved, and in that way they are analogous to the contemporary conditio humana. He causes a trace to speak and in the process urges forth an unarticulated truth that imprints itself onto the surface of the works and thwarts rational composition. Reichman creates an ambiguous and subtle play between private and collective memory, apparent idyll, and subliminal brutality.

In the work I Am Sorry Felix, but We Are Just Too Scared to Fly, A–N (2013–16), he refers to Félix González-Torres’s work Untitled (Vultures) (1995). This interaction makes incredible sense. González-Torres stood for the democratic dissemination of art, and thus for the subversive undermining of market mechanisms. But he also stood for empathy and had a great sensitivity to human particularities, since as a politically active artist he took a position on social issues such as AIDS, censorship, discrimination, and homophobia. Just like Reichman, González-Torres revealed the aspects of poetry and formal elegance hidden in political dynamics. Ariel Reichman likes to describe his own work as “poetical political,” which is revealed perhaps most memorably in this work. Shortly before his death, González-Torres had returned to photography, making his own ephemerality the subject of a series of black-and-white photographs. The series shows silhouettes of circling vultures just about to break apart, seen against the infinite expanse of the sky, “at once weightless and deliberate, poetic and deadly serious,” as Heiko Klass and Nicole Büsing describe it in Der Spiegel.5 Ariel Reichman follows the minimalist impulse of González-Torres and causes even more to vanish, so that his work looks almost like perpetual rain, further reinforcing the vulnerability already evident in its precursor. The use of the term “poetic” is quite appropriate here. In chapter seven of his Poetics, Aristotle writes: “By ‘beginning’ I mean that which does not have a necessary connection with a preceding event, but which can itself give rise naturally to some further fact or occurrence. An ‘end,’ by contrast, is something which naturally occurs after a preceding event, whether by necessity or as a general rule, but need not be followed by anything else. The ‘middle’ involves causal connections with both what precedes and what ensues. Consequently, well designed plot-structures ought not to begin or finish at arbitrary points, but to follow the principles indicated.”6 The title I Am Sorry Felix, but We Are Just Too Scared to Fly, A–N sums up the nonarbitrary part of this reference, in its expansion on the original with the possibilities of its interpretation, and underscores his own emotional reaction.7 Something similar can be recognized in And We Shall All Disappear, One Day (2010), which also refers to González-Torres. In the photographic diptych, an unmade bed can be seen only schematically—the shadow of a story that moves fleetingly past us. Elfriede Jelinek describes the fleeing in her foreword to Claire Felsenburg’s memoirs Flüchtlingskinder (Refugee children) as follows: “She ran after the fleeting now, touched it, captured it, when it wanted to run away, and the now became the past, as it always does, but she […] captured this fleeting thing that is already past by marking it, black on white, thrown simultaneously with herself into her own expanse, history behind, history in front of her.”8 I am interested in the method of approaching the material, memorably described here by Jelinek. We have the unmade bed of González-Torres, an emotional gesture about a relationship to a deceased person, and a political gesture toward private and public space in which same-sex couples had no right to a private sphere, after a 1986 decision by the United States Supreme Court. It is a marking of that which is fleeting: life. In Ariel Reichman’s work, in turn, the fleeting marks the slow disappearance of the self but also of individual and collective memory. And it is precisely this disappearance that is captured at the moment of disappearance, making it very clear that the disappearance itself cannot be halted. It is the moment in which the meanings of things overwhelm people and insight becomes possible. In Reichman’s work, human vulnerability obtains its appropriate place, and things regain their pathos. One might ask why this is so important, really. I think it suffices to look at the media, at the political and economic approach to empathy, and to look at the unresolved conflicts that under the contemporary status quo seem to be farther from resolution than ever before. Social forces have moved away from the human being, but solutions cannot be found without incorporating human beings in all their complexity.

II

After all, we’re at war. Endless war. And war is hell, more than any of the people who got us into this rotten war seem to have expected. In our digital hall of mirrors, the pictures aren’t going to go away. Yes, it seems that one picture is worth a thousand words. And even if our leaders choose not to look at them, there will be thousands more snapshots and videos. Unstoppable.9

The Clouds series (2016), paintings on canvas, looks at first like one of Cory Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds, which are direct products of computer technology. White spots against a blue background, moving across the image like clouds, with colors that evoke associations of a pleasant summer day. But clouds gather here as well. These works are based on photographs of the Iron Dome, an Israeli air defense system that shoots down airborne missiles launched from Gaza. Reichman took the photographs himself from a window in his basement, in Tel Aviv. At the moment the missiles explode, clouds form in the sky. These paintings work with the abstraction of war and the multitude of horrible images that are published daily and provoke little more than a shrug of the shoulders. Susanne Mayer writes, “It rightly raises the question of how to deal with this constantly rising flood of images. Not a new question, of course. From the outset, one aspect of the critique of modernity was [Susan Sontag’s] thesis that ‘modern life consists of a diet of horrors by which we are corrupted and to which we gradually become habituated.’ Such images can no longer be anything but a challenge to pay attention, to reflect, to learn—to examine critically the rationalizations for mass suffering offered by the established powers.”10 For Sontag, regarding the suffering of others is the quintessence of contemporary life.11 Sympathy, the thrill of sensation, outrage, or assent are now the facets of a dubious media experience, and so Sontag’s analysis too moves between voyeurism, shame, and empathy. But eshe also reveals the rift in which we find ourselves and also that damning the image does not really help; for example, the documentation of the Vietnam War in photographs helped to reinforce the anti-war movement. However, as the flood of information, which goes hand in hand with the flood of images, increases, people become less sensitive to such images of horror. Even actions that take place in our immediate vicinity provoke no reaction. This is also reminiscent of guided weapons, which are programmed to strike somewhere and yet no one has anything to do with it. Only when the suffering affects us personally are we in a position to feel it. Only in this situation does one become conscious of the suffering of others. This might also be described as a shift in reality. Ariel Reichman skillfully circumnavigates this problem by abstracting the violence rather than showing it. By doing so, he finds a persuasive metaphor for how images function today, on the one hand, and creates a belated and perhaps also more sustainable horror, on the other, at the very moment when the viewer notices and recognizes that what he or she is looking at is merely a camouflage. Two levels of reality meet in order to generate knowledge. He employs this procedure in several series: In 20/07/14 (2015), the camouflage-like abstract image is the visual information that missiles broadcast just before they explode. The title is the date on which just that happened—the recording used in the works is real. Brutality is neutralized here by beauty and reveals how the mechanisms of repression function. These works are a physical manifestation of the lack of tangibility in most of our interactions with war and violence. The series Reminiscing Virtual Landscapes addresses this theme sculpturally. The stele-like forms are based on a distorted image produced by placing a camera on a missile. This video was necessary to demonstrate its accuracy. The sculpture that ultimately resulted shows the chopped-up statistics that result from the explosion. Cast in ceramic cement and polished on top, the digitally generated 3-D prints produce a quasi-modernist totem of physicality. Reichman thus also manages to get the abstract computer image, which distances the viewer from real events, to return to the space as a physical, and therefore tangible, construct. The artist confronts the media images with an urgently needed presence, and thus seems to give form to Sontag’s dilemma, as described by Mayer: “Contrary to her earlier assessment that the daily flood of images dulls us, Sontag now insists on the necessity of images. Wars of which there are no photographs are forgotten, she says. Surely true. Photographs cannot prevent wars, also true. And victims want us to see their suffering, says Sontag.”12 But Mayer adds a caveat to these statements:: “Except, a tricky question: Who is the victim, who the perpetrator? And why?”13 Presumably, the question can only rarely be answered. Here, too, Reichman’s personal vita comes into play. With The Artist’s Army Boots (2015), he exhibits the army boots he wore during his mandatory service in the Israeli military. The shoes were willfully and seemingly aggressively destroyed by the artist and serve as signs of his own involvement in that which we would like to have answered more simply. Even the question “why” opens up a complex field of connections, which, in the meantime, are so mixed up with one another that there seems to be no escape. On the contrary, we seem to be returning to the drawing of political borders—a concept that seemed outdated, at least in Europe, for a brief period. In several of his works, Reichman refers to drawing borders, exclusions, and even occupations. In 2009, he occupied the rooms of the PROGRAM project space in Berlin with the durational performance Legal Settlement. When does an occupation, an action, an enclosure become legitimate and how is it legitimated? Reichman gradually set up a home, invited friends to dinner, and showed videos of various performances in the exhibition space. I have not seen this performance, but judging from the photographs, he turned the sterile white cube into a habitable place where it was pleasant to stay; that is, the occupation took on a positive touch. But this statement is perhaps undermined by the fact that the videos shown were of his earlier performance works concerned with military and religious training, as well as the installation Blowing in the Wind (2009). In this work, a mechanically powered white flag stands in the room, and a projector beams on it. In the projection, the waving flag is black. Bob Dylan wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1962) as an antiwar song. The lyrics consist of a series of rhetorical questions about the meaning, or rather meaninglessness, of war. It is worth nothing the musical context in which this song was written: “He [Bob Dylan] manages with his somewhat brash, raw style of singing to put his finger in the wound without too much moral finger-pointing. Although his voice is nearly toneless, it has a remarkable intensity. This somewhat strange mix of casually sung indifference and simultaneous urgency is what makes the performance so remarkable.”14 This is also true of the way Reichman works. The more deeply one goes into the history of song, the more richly faceted its references becomes. Dylan modeled his song on the gospel song “No More Auction Block,” whose lyrics refer to the slave auctions in which abductees from Africa were sold to white estate owners. At such auctions, familial connections were completely disregarded; indeed, families were often deliberately split up to break their spirits. The “auction block” was the platform upon which the fate of soon-to-be slaves was decided. The phrase “no more auction block for me” thus expresses this hope and desire that the yoke of slavery, symbolized by the auction block, can be thrown off. Today, children are once again being separated from their parents at borders. Of course, this context was not part of the original intention of Reichman’s work, but it lends an additional gravity. It feels like being on a Möbius strip again, a diversity for which no orientation can be found, in which we are going in circles around the absurdity of contemporary life, which repeats itself and in which it seems difficult to convey the effects of learning and social coexistence.

But let us return to the borders that are now being raised. Reichman himself describes it in an interview: “My first memories were of my brother telling me, ‘This bus you can take. This one you can’t. This park is for you. This park is not for you.’ It was totally separate.”15 This feeling of drawing up borders, which has accompanied him since his earliest childhood, is also found in a wide variety of works: In Electric Fence 1 (Kerry Road) (2015), one sees in the background of the photograph a bush submerged in darkness; in front of it stands an electrically charged wire fence, which was used as lighting for the photograph and runs the full width of the photo. The entire composition signals danger and drawing borders. Something has to be protected from something else. In another work from the same series, Electric Fence 2 (Kerry Road) (2015), the nature has been removed from the image and only the wire remains. This abstraction recalls his coming to terms with González-Torres: the subject matter is just as disturbing; it is merely nicer to look at. The same is true of the photograph Wire and Tree (2017), in which part of a tree is seen in the background, its grain in particular stands out. Because of their age, trees can function as conveyors of history, which in this case is entrenched behind barbed wire. There is another demarcation from nature in Wire and Grass (2015), this time nature is marked off by barbed wire. These works can be interpreted in many ways, but here, I merely wish to emphasize the binary aspects. Two sides are shown, immersed in light and darkness. It is not clear on which side one should stand; rather, it indicates that every border is fabricated and is distinguished by negation and the invisibility of the real. Perhaps the series Untitled Window Bars (2015), based in part on window bars found on Auguststraße in Berlin, but also on Kalisher Street in Tel Aviv, can serve as an indication that windows one cannot see out of are not a good idea, since closing oneself off and refusing visibility cannot be the foundation of a community based on solidarity.

The title of the present volume is The Space between Here and There. What sort of a place is Reichman alluding to? What is the space between here and there? What happens in the interstices, in the transitions, at the fences, where no one is watching very carefully but where crucial things happen? It is a place in between that is not necessarily polarized but that is more complicated than it can ever be on either end, since many levels of meeting come together here in an undifferentiated way. It is located between the political and the private and between the intimate and the public; hence, it is also a place where everything still seems open, a place that is inherently a space of possibility in which one can think and act freely. Not coincidentally I am thinking of the small sculpture And All She Wanted Was to Bring Him Home (2015), in which a bird is slowly but surely trying to break through a wall to get to the other side. Spaces of possibility are perceived, conceived, and lived places whose function remains mutable, flexible, and open. They permit social and economic experiments and give people room for different experiences. It is not surprising that Reichman foregrounds migration and threshold states, since these represent a big part of his own story. At the beginning I gave a purely positive connotation to this space in between, but it too is ambiguous. A space in-between is also associated with uncertainty, with danger, and sometimes also with a lack of belonging. Likewise, Reichman also shows that spaces can be separated, that there are conflicts and violence. But he does so in a poetic way. His art does not allow affirmation to wash over us, but encourages us to start thinking and learn to see. Only that which we do not understand stimulates thinking. Reichman’s work resists expectations and moves toward complexity; precisely therein lies its quality. In the small wall piece Trying to Draw the Star of David with My Left Hand (2010), the right-handed artist tries to draw a Star of David, the symbol of Israel and of Judaism, with his left hand. It works only up to a point, but what it touches on is the attempt to do just that by adopting a perspective opposite from the normal approach. It reveals the fragility of the whole but also the possibility that the norm can be changed at any time. Movement is possible. His artworks seem like enigmas, and the more deeply one penetrates them, the more enigmatic they become, since none of them offers the solution it promises. Reichman does not intend for his art to solidify convictions, but rather to cause them to waver, thereby activating a process of cognition that is never truly finished. It is certainly kitschy to end with Bob Dylan’s lyrics, but that does not make it any less true:

How many times must a man look up

Before he can see the sky?

Yes, ’n’ how many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry?

Yes, ’n’ how many deaths will it take till he knows

That too many people have died?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.

Jacques Rancière, The Aesthetic Unconscious, trans. Debra Keates and James Swenson (Cambridge, MA: Polity, 2009), 3.

Press release from Zeppelin Universität on the exhibition Ariel Reichman, 2012, https://www.zu.de/universitaet/artsprogram/kuenstler/Reichman_kuenstler.php (accessed May 23, 2018).

Rancière, The Aesthetic Unconscious, 59–60.

See ibid., 61–62.

Heiko Klaas and Nicole Büsing, “Vom Museum in den Mund,” Der Spiegel, October 6, 2006, http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/kuenstler-Gonzalez-Torres-vom-museum-in-den-mund-a-440641.html (accessed May 27, 2018).

Aristotle, The Poetics of Aristotle, ed. and trans. Stephen Halliwell (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 31–47, esp. 39.

See Aaron Bogart in a press release from the PSM Gallery on an exhibition at abc-art berlin contemporary, I Am Sorry Felix, but We Are Just Too Scared to Fly, Ariel Reichman, September 2016, http://myartguides.com/exhibitions/ariel-reichman-iam-sorry-felix-but-we-are-just-too-scared-to-fly/ (accessed June 27, 2018).

Elfriede Jelinek, “Das flüchtige Jetzt (zu Claire Felsenburgs Aufzeichnungen),” in Claire Felsenburg, Flüchtlingskinder: Erinnerungen, ed. Rosemarie Schulak and Konstantin Kaiser (Vienna: Theodor Kramer Gesellschaft, 2002), 10–11.

Susan Sontag, “Regarding the Torture of Others” (2004), in At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches, ed. Paolo Dilonardo and Anne Jump (London: Penguin, 2008), 128–42, esp. 142.

Ingeborg Breuer, “Verstörende Kraft: Susan Sontag über Photographie,” in Deutschlandfunk, February 11, 2004, http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/verstoerende-kraft.700.de.html?dram:article_id=81653 (accessed May 27, 2018).

See Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003).

Susanne Mayer, “Hinschauen. Fragen,” Die Zeit, August 7, 2003, no. 33, revised on July 1, 2014, https://www.zeit.de/2003/33/L-Sontag (accessed May 27, 2018).

Ibid.

Jochen Scheytt, “Popsongs und ihre Hintergründe: Bob Dylan: Blowin’ in the Wind,” 2015, http://www.jochenscheytt.de/popsongs/blowininthewind.html (accessed March 16, 2018).

Ana Finel Honigman, “Interview with Ariel Reichman,” ArtSlant, May 2009, https://artslant.com/global/articles/show/7394-interview-with-ariel-reichman (accessed March 16, 2018).

Raphael Zagury-Orly

OUR DIALOGUE - AT THE LIMITS OF THE NAME

BY RAPHAEL ZAGURY-ORLY

The work of art, if such a thing exists in its generality, when it arrives, when it occurs to us, always dictates more than what it presents. What arrives as a “work of art” in its singularity defies all binary logic and flouts all the boundaries that traditionally define, form or determine what is or what is called a “work of art”. What occurs as a “work of art” challenges the very thinking of this word and what it could identify – the unity of a corpus, the title, the framing, its tradition, the history to which it supposedly belongs to. It is as if in the face of the singular eruption of the “work of art”, the very idea of a History of art appears as a tale, a certain legend or narrative myth. The History of art seems suddenly as a construction, almost ridiculous. However inevitable it, this History, remains. What happens in the “work of art”, when and if it happens, is an overflow, an excess, a surplus that spoils all the traditional boundaries and divisions between the singularity of the “work” and the “history”, the context, the “scene” in which it manifests itself. In other forces us to extend and enlarge, always more, to search for the very idea and concept of the “work” as well as of its “history”. In the face of this “work”, we possess no predetermined idea or concept. Its history can never pose a finished corpus, some content enclosed in its frame or presentation, but something akin to a differential fabric of traces and offshoots referring indefinitely to something other than itself, to other differential traces. Thus, the “work of art” exceeds incessantly all the predetermined limits and circumferences assigned to it, without however drowning in an undifferentiated homogeneity, an indistinct void. Rather the “work of art”, when it occurs, bends its limits and thereby producing altogether more complex, multiplying and differentiating strokes and lines than what is enclosed in its own presentation and intentionality. And this persistent excess comes as a certain shock generating endless efforts to dam it up, to resist it and rebuild old traditional binary partitions and ultimately blame and condemn what can no longer be thought, seen, heard or felt without confusion.

But one must ask these questions: what are the limits of a “work of art”? How have such limits surfaced and given way to the possibility of judging it? How do such limits ever come about? And these limits, can they be avoided in any way?

These questions cannot be approached frontally or directly. They only arises whilst and with the occurrence of the “work of art”: obliquely through “a narrower channel, but one that is more concrete as well”, to quote Harold Bloom. They arise on the edge and at the limits of what we have come to name a “work of art” according to the age-old paradigms of truth, the intelligible and the immutable. If we had to situate the “work of art” it would be at the limits of the horizon of meaning and the deployment of essence.

The dialogue between Ariel Reichman and I always revolved around these difficulties, and always stood on the threshold of these limits. We could even say it grew within a type or form of embarrassment in the face of the necessity to say of a “work of art” that it is this or that whilst also and at the same time saying of it, the “work of art”, that it is both this and that. To go to the limit of this infinite discussion, we could say it remains concentrated and focused on the impossibility of naming whilst always requiring to name the “work of art”. A sort of unsettled dialogue on the countless aporias which occur when we are constrained to name that singular eruption of a “work of art”, singular eruption which never simply converges in a name, in one name but which remains always foreign, exterior, rebellious to all names.

If I had to say something firm of our dialogue, I would suggest that it is haunted by a common discomfort, a common feeling of awkwardness over the necessity to choose between two logics of naming, to decide for one over the other, to affirm one and reject the other, even though both these logics certainly, and at one point, converge: a logic of inclusion – including all in the nameable – and a logic of exclusion – and therefore segregation between that which is considered worthy of a name and that which is rebuked into the non-nameable. As if our thinking together, our speaking to one another, was also traversed by an altogether heterogeneous space from which both these very logics, and also the alternatives they can each offer, would become possible and yet, at the same time, remain undecidable. As if our dialogue thus already cared profoundly, at once and simultaneously, for all the possible logics past, future, present of naming and yet never give itself the right nor the force to elect one over the other, to embody one without the other, to fix therefore always more than one unique name.

Our dialogue – yes I would suggest it also – erupts from this curious and ambiguous third genre without genre. A place or space without place nor space. An ambiguity which never ceases to mark, to determine every event possible or even imaginable and yet, at the very same time, instant or moment, remains un-marked, un-determined in itself. Towards which future? Towards which dream or vision? One perpetuating, for the singular eruption of the “work of art”, something altogether different than a name, perhaps or maybe wholly other than possible names.

Ariel Reichman.

Goodman Gallery, Cape Town.

There was a bell installed in the wall above my parents’ bed. Each morning, my mother would ring this bell and the sound would transport itself into the kitchen. A couple of minutes later, Maria would enter the bedroom and serve “tea for the master and coffee for the madam”. She always referred to my father as master and my mother as madam. Actually, that is how she would refer to any adult living in or visiting our home.

I was born in apartheid South Africa in 1979. Maria was a second mother to me. My parents claim I could speak fluent Zulu as a child, but I have no memory of the language. Maria lived with us in a small bungalow in the backyard (such bungalows are being renovated in recent years and rented out to tourists via Airbnb). Although our relationship was extremely intimate, I have no knowledge regarding Maria’s background.

I do not know where she was born or where her family lived. I do not even know if she had children of her own whom she might have left behind in order to help raise me and my siblings. I do not know her family name or when she was born. Neither do my parents.

I have wondered how it could be that I know nothing about a woman who was like family to me. Surely this is just the naive view of a white child, but during apartheid this reality was quite normal in South Africa. My parents say they treated her with respect and care and in comparison to other white households this may be true. (In the homes of friends of mine, the “help” was not allowed to use the house furniture or cutlery. They were allowed, however, to bathe the family infants.)

Knowing this does not eliminate my sense of guilt. Maria had no social rights nor was she paid a reasonable salary, if any at all. Yet she was and remains my beloved Maria. In 1991, my family immigrated to Israel and all contact with Maria was terminated. To date I have had no knowledge of where she could be since then.

In 2015, I was invited by the Goodman Gallery to participate in an exhibition with a performance-installation titled Tea for the Master and Coffee for the Madam (2010). Installed in the gallery space were two chairs, a bell, and a framed C-print showing myself as a child tied to Maria’s back while she is cooking in the kitchen. One could assume from this photograph, or from others, that Maria is my mother. Throughout the duration of the exhibition, visitors were invited to ring the bell and in the gallery’s kitchen, I would prepare tea for the men and coffee for the women, serving them in the exhibition space while wearing the dress that Maria herself used to wear. The visitors are welcomed to sit on the chairs as they drink their served beverages. At some point during the exhibition, a young black couple said to me, “You know, Maria, like so many others, is our mother.” At the exhibition’s opening, a women entered the kitchen and was intrigued to talk to me. I told her about the piece and the story of Maria. After some minutes of discussion she suddenly realized that she knew my parents and that at the time her children had studied for their Bar Mitzvah with my father, at our home. She said that her “girl” Dora would drive the children to my house and that she must have known Maria. This surprising and exciting news led me to meet Dora, who then joined me in my search for Maria. Dora remembers sitting with Maria in the kitchen while waiting for the young boys to finish their lesson. She hadn’t seen or heard from Maria since we left South Africa in 1991. The search for Maria, although doomed to fail—as I had absolutely no concrete information except some family-album pictures (that were as well more than twenty years old), took me on a journey through post-apartheid South Africa. Accompanied by my camera and Dora, I encountered suspicion and fear from the families still living on the same street in Saxonwold, where I had once lived. In addition to this search, I painted two hundred paintings of Maria and hung them around the city hoping that a family member might see it and recognize Maria. As I came to realize my chances of finding her were so very slim, this act became instead an homage to all these women who left their own families in order to raise white children.

Wherever you may be, I love you, Maria.

Drorit Gur Arie

1200 kg dirt.

ON RANDMONESS

BY DRORIT GUR ARIE

A blossoming garden was installed inside the walls of the Yad LaBanim Memorial House, inside the collection of the Petach Tikva Museum of Art, which is located in the first of its kind commemoration sites in the country. Door opposite door the two come together. Naturally, the term ‘house’ is both private and public. This attempt at hybridizing the personal and the public in one building was reflected in this building since its inception, and was a novel idea at the time. It is an act of embodying the ties between the past and present. In the wish to create a living site, the memorial house, built as a site for memory and commemoration, was erected not far from the city's center, hence not completely separated from the sounds of everyday life.

Ariel Reichman’s 1200 kg of dirt proceeds to perform a similar, almost painful act of hybridization of nature and culture, of the inanimate with the living, of growing and decaying, nurturing and killing; the bugs eating away at the garden plants, threating the lives of the artworks chosen by the artist as an active part of his work, are all doomed to die. Internal contradictions reside and thrive simultaneously in this installation that moves the soul, is breathtakingly beautiful and heartbreakingly sad. The struggle of the living and the dead is expressed in the etymology of the Hebrew word for space ('halal', or 'void'), that is also the term used for those killed in military action. 'Halal' is almost synonymous with the word ‘fallen’ used to designate those whose life cycle was cut short. ‘Hallal’ also refers to an exhibition space, which is a ‘graveyard’ for art objects but also a burgeoning place for art viewers.

In Reichman’s ongoing installation the two types of ‘voids’ are situated side by side: the names of the fallen are engraved forever in the stone in the opposite room, as ar tworks and chests filled with land lie silently on the gallery floor evoking graves. Then something happens and the garden appears as a breathing, living world. Light bulbs nourish its plants ensuring they continue to thrive, wind chimes and colorful weathervanes that are placed among the plants create sounds with every visitor’s movements, and even the iconic statues of fallen soldiers and the magnificent flower drawings from the museum’s collection seem to show signs of life for a moment when viewed in the context of the plants and flowerbeds surrounding them.

Randomness resides in this installation, a kind of randomness that is present in other works by Reichman. Death in the battlefield is often quick and random. The fate of the garden lies in Reichman’s hands; ‘the gardener and the griever’ who tends a garden which conceals personal stories that deviate from the cruel and fixed order, like a military formation for the heroes brought to rest in military cemetaries. A single yellowing leaf in one of the planters quivers between life and death while other plants attempt to reach out beyond the confines of their containers. Earth is dispersed in the exhibition space, perhaps a moment before it will be collected into a planter, or before it is swept off the black marble gallery floor. Ostensibly, chaos govern order here: dead plants will be replaced by fresh ones; art works will be taken out of the gallery for a while to be conserved. The day the show opens will be just another day in Reichman's gardening process, which will end with the closing of the exhibition in a number of months.

What will become of the garden? Time will tell.

Yael Guilat.

Petach Tikva Museum of Art.

Yael Guilat: How did the garden come to be?

Ariel Reichman: The process began when I was approached with the offer to suggest a project incorporating The Museum of Petach Tikva’s art collection. This was a new direction, a type of procedure that is foreign to my natural work processes. I began looking through the collection, going over its many works, when I realized that a large portion of it consists of works dealing with mourning, war and nature. Actually, the works in the collection created a “natural” link between mourning and war and landscape and nature. These issues, incidentally and deliberately, are ones I deal with in my own work. Even prior to this project I was very interested in military graveyards. And although I haven’t lost a brother or come from a bereaved family, I have visited quite a number of military graveyards.

YG: It’s interesting that you said “brother.” In doing so you placed yourself in a very active place, in that you see yourself being able to take that place. Yeshayahu Leibowitz once said that he is frequently asked if he stands during the commemoration siren on National Memorial Day. He replied that he did, as he was part of the public, of the society. And when Leibowitz said that, with all that we know about his opinions toward institutionalized ceremonies and commemoration, he emphasized that if he would not stand on Memorial Day, he would lose his right to criticize society.

AR: Maybe I say brother because that is where my interest began. My older brother lost a close friend in South Lebanon. Later I became curious about his story, which was very mythic and heroic, even worthy of a military citation award. I thought a lot about my brother being “a hero,” a source of family and national pride. This also relates to the fact that I come from a Zionist-religious home, and that these are the values I grew up on. One of the most striking things I encountered at the graveyards were all the empty lots waiting to be filled. I realized that as opposed to monuments, that are historical places, military graveyards are very much alive and active.

YG: That is exactly the point that characterizes the Israeli discourse of bereavement – that it is open. Then the question arises about the possibility to commemorate in a place in constant flux. In this context, the way you treat the ties between the living garden and the Military graveyard gains even more validity.

AR: I think that these tensions are reflected in the relations between the ways military gardeners look after the plants in the graveyards as a whole, and the very personal nurturing, almost ritualistic, of the graves by family members. The military graveyard’s beauty is disturbing. Obviously it is very ordered, and the areas of chaos are small and private. Other than the very specific types of plants planted in the grave’s flowerbeds, there are also objects, statues and even balloons on birthdays. The place interests me, its stand between the political and institutional and our intuitive human need to turn loss into something unique, personal.

YG: The military graveyard has two main symbolic functions: one relates to the ritual involved in the bereavement process of the family; the other is tied to the national and heroic aspects of the commemoration, as in “memory,” with its look toward the future and not the past, its instructive quality. This is exactly the difference between civilian graveyards and military graveyards – in that the latter prepare the ground for the future. From this view the small interference of the living garden creeping upwards or to a neighboring grave disturbs the order; the temporal disrupts the eternal.

AR: Between the past and the future, it seems that the bereaved families at the military graveyard are trapped in a continual present, enslaved in a ceaseless act of mourning; that there is no legitimacy to overcome it and return to life, but like the myth of Sisyphus, families are sentenced to tend the garden forever. An eternal present tense.

YG: This present tense is eternal also because if there is any relief from the personal grief, it is burdened with a continued national mourning – ceremonies and memorial days. So that even when on the personal level parents have managed to hang on to life and continue living, the national stance keeps forcing them back into the bereavement ritual and mode. And in the ritual of mourning the garden is the place that legitimizes the act of grieving, it is almost the only place where parents are left alone. Perhaps because the garden is non-textual, in this regard it seems less threatening, it doesn’t state a claim or anything that should be debated in the court of law. The individual flowerbeds were placed out of a need expressed by parents in the 1970s. That is, it’s not that there was some thought about the need to allot a place for personal grief, but that there were flowerbeds on the graves and people began tending to them or planting in them something from their home gardens. Since then, for over 40 years, the flowerbeds have come to mark the conflict between the continual therapeutic aspect of the parents, and the institutionalized aspect that wants everything ordered and covered. In many regards, the act of gardening both ratifies the myth of commemoration and the continuation of life.

AR: One of the things I realized during the six months I spent working on the garden is that it required I develop a gardener’s awareness. You have to tend to it every two or three days, weed, clean it up. While it is therapeutic on one level it’s also very demanding.

YG: That’s the difference between a garden and nature. The garden is culture. What perhaps separates the standard gardening of military graveyard is that they are maintained by military employed gardeners who work according to local conditions. The private gardens, in contrary, need constant attending. The difference is that between cacti that need very little care and types of foreign or tropical plants that demand constant attention, and yet are the types of plants that characterize the small flowerbeds.

AR: What will really happen when the bereft parents will also go?

YG: When Shoshi Waxman and I were researching this subject, we understood that what’s set in stone is set in stone and the gardens, perhaps, will disappear. Even if parents or relatives stop visiting the grave the remembrance still continues. In the chains of national memorial mechanisms, in the final score, commemoration is stronger than individual grief. When talking about remembrance there is a divide between soft memory and hard memory. Setting in stone is hard memory while the non-materialistic ritualistic commemoration is considered soft memorial. Surprisingly it is the soft memorial that threatens the hard one and eats into it.

AR: It’s nice this corroding, and brings me back to the pest-control procedure undertaken in the exhibition space under the orders of the museum’s conservator. This might sound very naïve, but in putting the garden in the gallery I also brought in animals, that now must be poisoned and actually killed. This very un-protective act stems exactly from the fear that the soft memorial act will spread out – will reach the wall and damage a work from the collection that the museum’s task is to commemorate, to preserve it.

YG: This tension was known in advance, was it not?

AR: It didn’t cross my mind; I didn’t think about this facet in advance – that there is humidity, light, bugs that might potentially damage the collection. I chose the works from the collection with a great deal of respect. I consider it an honor to show works by Moshe Gershuni or Anna Ticho and it is very moving. The idea was that it is possible to create a uniform space in terms of the hierarchy of things shown in it, and what sort of relations form between them. I was not aiming at intensifying the tension between the garden and the collection, but promoting a kind of harmony, an opportunity for cohabitation, where the statues accept the garden’s overgrowth as a given. This is not a diminishing act, but an attempt to find the place where the works are “comfortable.” When I look at Dov Feigin’s Palmach statue, for example, I feel it is more at home when not placed on a pedestal. And if the weathervane is treated like a statue, this is only due to them sharing a partnership between them in the space.

YG: I think you are raising another issue here. That the works donated to the museum where not given as works of art but as offerings. In the same way that religious gestures changed the ritual of a living offering with a material one, which is treated like a sacred relic, like a remain of the live body, one that has some majestic quality. When a statue is placed on a headstone it is not for its artistic quality, but as a gesture of giving, an offering symbolizing the victim. In military graveyard there is no hierarchy. You can see a vest, a cap, and also the most beautiful poem by Yehuda Amichai or a letter written by a friend. These are gestures that connect and give the departed presence, but they are unsupported on the artistic level. From this angle, a weathervane and Feigin’s statue in your garden are on the same register. And in the wider context of the collection – many of the works in it were given by family members wanting to honor the memory of their loved ones through the gift.

AR: In a few conversations I had, people said the garden was dominating the statues. I don’t see it that way. The garden isn’t domineering, which is a violent term; it’s just doing what it’s supposed to be doing.

YG: But your act is violent and that can’t be ignored. The soft memorial, the eroding, is also violent. Violence is not only being hit on the head with a sledge hammer, it can also be expressed in different forms and existences. Look, everything in the world depends on placement. Earth, for example, when it’s in a flowerbed or a desert is earth in itself, and when it’s in the house it is considered filth. It’s true that in the contemporary art framework we are familiar with Land Art that thought of the materialistic context and asked to bring in the world outside. Land has been brought into exhibition spaces in different ways. But your act was not done in this context but with a very clear aim and a wish to highlight the battle between nature and culture. In your work this confrontation does not take place symbolically (as is usually the case with art), it actually occurs – there are stickers meant to trap flying bugs. You created a place that works like a total shape, a place that is sensual and physical as well as symbolic, and you are constantly facing the meanings of this conflict. The basis of this clash is your entry to the space, where on the one hand you have what you brought from the military graveyards and on the other – the works from the museum’s collection. These are two different forms of commemoration that you have faced-off and asked how they work together and what the one reveals about the other. You put something here in strong relief. It is strong but also soft, thus allowing people to talk about these things. Your discussion is not in the face of bereaved families, and in this meaning it is clear that you’re dealing with this not from the place of personal grief, but questioning our existence in space and the ways we operate our historical memory, our memorial rituals, the conflict, and what is called conflict management. In this respect your work touches on the social, political and artistic and involves congruence between the institutionalized commemorative DNA and what is happening in the country. The way you chose to deal with this subject allows both those who have a direct say on these matters and those who have only an indirect one to open up a discussion.

AR: When the garden was in my studio and people came to visit, I heard a wide range of reactions: the basic one was “fun” – here we have a nice scented garden, with the smell that gets stronger when the garden is watered, and a longing to spend time in it. Another reaction came from those who felt that it is very powerful, some people cried, others were very moved, like something had hit them and they didn’t know what. Looking back it turned out that those who had a personal link to this type of bereavement felt this emotive baggage while those who are not as familiar with mourning could just enjoy the green garden, its liveliness, its beauty. When I am at a military graveyard this is the kind of paradox I experience – the feeling that I’m in a beautiful place, and also feelings of sadness, anger, almost a need to protest; ambivalent and unresolved feelings. A movement between empathy, aesthetic joy and rage.

YG: You brought certain objects from the military graveyard to the gallery, while refraining from others. One common object in the graveyards are the portraits of the dead. I know that the museum’s collection includes these objects that you didn’t put to use. This very clear avoidance attests to your stance on the collection and that you are dealing with art. There is a sense that you don’t want the work to look too much like a graveyard.

AR: I deliberately avoided faces. There are many portraits of the dead, or pictures of grieving mothers, and other objects that ostensibly belong to the commemoration discourse. But I wanted to avoid subjectivity and specifically the question as to whom the garden belongs.

YG: It seems as if what enters here cannot leave.

AR: Yes. And everything happening here happens now. When I thought about a certain painting I thought of its links to the garden in the most physical and aesthetic terms; for example, Gershuni’s painting reminded me of the plant growing besides it. Like a reflection. Not only from the formalistic view, I wanted to put the nature of the collection into the nature of the garden. In the Memorial Garden, just outside, there is an army tank standing like a foreign body, and that is exactly what I wanted to avoid in my garden. I wanted to install in it things that seem to fit easily. The flower drawings sit well with the real flowers. There isn’t a clash but a dialogue.

YG: What about the benches?

AR: The benches belong to the museum and I let them in. Generally, I didn’t put any artistic object in the garden that is mine – I didn’t sculpt or paint. I performed gestures but did not create anything except two low benches. Military graveyards have places suited for sitting a sole person, not for guests, for one being. This is a very subjective recollection of the individual and not of society. I used sesame tiles because they express the will to bring the private, homely space into the public realm embodied in the museum collection.

YG: In military graveyards too, the grave plot is transformed into the child’s room. Objects are brought there, arms and personal items.

AR: it was important for me that being here would raise more and more things, that the identification wouldn’t be direct, but that different layers would float and rise up.

YG: I am looking at the rows of light above.

AR: That is the order, the grid.

YG: It resembles the grids in greenhouses. And really, we are actually in a greenhouse and there is nothing more suitable than that to talk about the way nature can be cultivated with artificial light and heat. Is there an explanation for that?

AR: It’s the gardener’s version.

YG: Technical considerations created a certain aesthetic and order – top and bottom, heat and cold, nature and culture. We meet this binary here all the time, and contrarily, an attempt to break it down.

AR: When the instructions from the conservator arrived, a negotiation began – the plants need light, the paintings shade, how is this to be handled? Most of the experts we consulted didn’t think the garden would survive. These are plants that need light. What amazes me is not only that they didn’t die, but that they are thriving here.

Hito Steyerl.

IBB Prize.

BY HITO STEYERL

The world vibrates in Ariel Reichman’s works. Objects transform into confusing or dismaying feelings. His practice is about human vulnerability as well as of the moment at which the senses of things overwhelm people. In Japanese aesthetics, the term mono-no-aware was shaped: the pathos of things, empathy with them, and the consciousness of their momentariness. Reichman’s works are characterized by this sensitivity. They draw a map of intensive sentience’s, the influence of a conflict on senses, feelings and perception.

Monograph.

Distanz Verlag.

The Space Between Here and There

Distanz Verlag

Format: 16.7 × 23.7 cm

242 pages, 181 color images, Hardcover

ISBN: 978-3-95476-237-8

Design: Gymnasium

Price: €34.90

Working in a wide range of media from installation, film, and performance to photography, drawing, painting, and sculpture, Ariel Reichman (b. Johannesburg, 1979; lives and works in Berlin) explores differences in the concepts of reality between spaces that are commonly understood as the public sphere and one’s intimate surroundings. Reichman is in search of a liminal space that is neither.

He proposes to underline the physical and mental state of living in between outside and inside. Liminality has been the focus of Reichman’s research and artistic practice. His work unfolds multiple layers of meanings and narratives that question one’s existence in space both physical, political and conceptual. Described as ‘conceptual expressionism,’ Reichman’s art offers an unsettling contradiction that challenges one’s own physical and symbolic presence as a viewer, and yet draws one into a physical experience of the work. This book is the first monograph on the artist and presents works from the past ten years. With essays by Bettina Steinbrügge, Hito Steyerl, and Raphael Zagury-Orly.

Catalog.

This is Worse. 80 pages.

Design:

Gymnasium Design Office

Text:

Bettina Steinbrügge

Johanna Adam

Printing and Binding:

Magentur

This publication is not for sale.

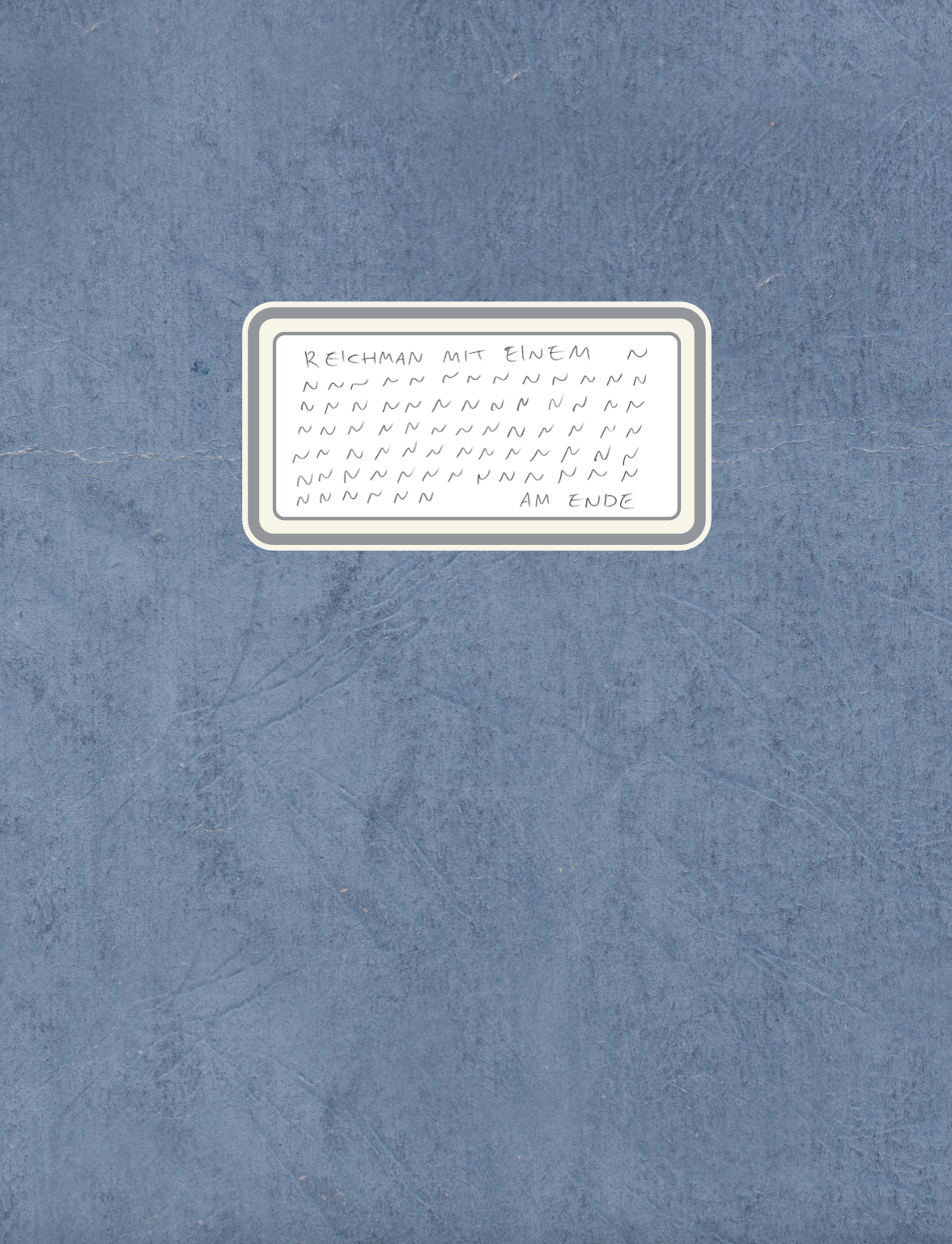

Sammlung Haus N. Heft Nr. 60.

Texts to the World

as it is and as it should be Textbook No.60

You can`t buy Texts to the World – you can only get them as a present.

Publisher:

House N Collection, Kiel/Athens

Idea and Concept House N Collection Content:

Ariel Reichman

Interview partner:

Jackie Grassmann

Editor:

Tamaris Vier

Link to publication:

http://www.sammlung-haus-n.de/pdf/heft_60.pdf

Collectors choice.

Lucida Journal.

Oda Bhar.

Morgenbladet.

Writer.

New York Times.

Also in the Frame section, Berlin’s PSM gallery will introduce the South African-born artist Ariel Reichman to a New York audience.

“I wanted to create something especially for the venue that hopefully provokes a continuous relationship with the scene here in New York —with curators, institutions, or collectors,” said Mr. Reichman, who came to the city for the first time a month ago to prepare his garden installation for Frieze.